“The old time people used to say that the Barbados Railway was mentioned in the Bible, among the creeping things of this earth”.

“The Barbados Railway 1881-1937” by Peter Murphy was shared by Robert Badley who found a copy in his father’s papers.

The author Peter Murphy has given his permission for BajanThings to re-publish “The Barbados Railway 1881-1937” which was originally published in the Canadian Railroad Historical Association magazine: Canadian Rail in Issue 403, March-April 1988 on pages 39 to page 51.

For a timely change at this time of the year [the end of the 1987/88 winter in Canada] we are pleased to take you to the Caribbean Island of Barbados. Most easterly of the Caribbean Islands, Barbados has long been a favourite “sun destination” for thousands of Canadians trying to escape the winter blues. Located in the southern Caribbean, Barbados measures 14 miles wide by 21 long and has an area of approximately 166 square miles. The population of Barbados is approximately 275,000 friendly natives; this is expanded in the winter season by the addition of several thousand tourists who visit the spectacular beaches and beautiful scenery.

To the visiting rail enthusiast, there is one additional point of interest, the local Barbados Museum, and if time permits, a day spent exploring the old “Barbados Railway”. Several local journal and magazine articles have been written about the Barbados Railway, nostalgic in nature they often speculate as to the nature of the tourist attraction that would be, should the railway exist today.

Barbados had up until its independence in 1966 always been an English colony since its discovery in 1637. In the year 1845 railways in England were booming and men thought they saw unlimited possibilities in the development of the iron road. Public roads in Barbados were in terrible condition and when a survey was made, it was decided that the construction of a railway was indeed feasible.

The first attempt at raising capital fell through, the second attempt in 1873 saw a proposal by Joseph A. Haynes of Newcastle, Samuel Collymore, John Inniss, David Da Costa and others join in writing subscriptions for 20,000 shares at £5 each in a company formed to build a railway line from Bridgetown to St. Andrews. In 1878 the act was amended to permit promotion of the proposed railway in England.

The famous light railway engineer Robert Fairlie visited the island and prepared a new cost estimate. A revised Fairlie report was published by the directors in the spring of 1877 and called for the railway gauge to be 3 feet 6 inches, the passenger cars would be in the American style of the period. Seven stations were planned over the 21½ mile line and on Saturday, 23rd June 1877 the first sod was turned by Lt. Governor Dundas.

H.E. the Lt. Governor was presented with a “painted barrow and spade’ in a short speech “he expressed the pleasure he felt in performing the task allotted to him, and congratulating the Directors and the Colony on the inauguration of an enterprise which he felt sure would not fail to promote the interests and prosperity of the Colony. He proceeded in a workmanlike manner to trundle his barrow to the edge of the embankment and deposit the first barrowful of earth amid three hearty cheers from the spectators and a large body of labourers who will find employment on the works”.

The Barbados Railway stations included:

- Bridgetown – 0 km (0.0 mi)

- Rouen – 4.0 km (2½ mi)

- Bulkley – 8.9 km (5½ mi)

- Windsor – 11.3 km (7 mi)

- a Branch to Crane – 14.3 km (8⅞ mi)

- Carrington – 14.5 km (9 mi)

- Sunbury – 16.1 km (10 mi)

- Bushy Park – 17.7 km (11 mi)

- Three Houses – 20.9 km (13 mi)

- Bath – 25.7 km (16 mi)

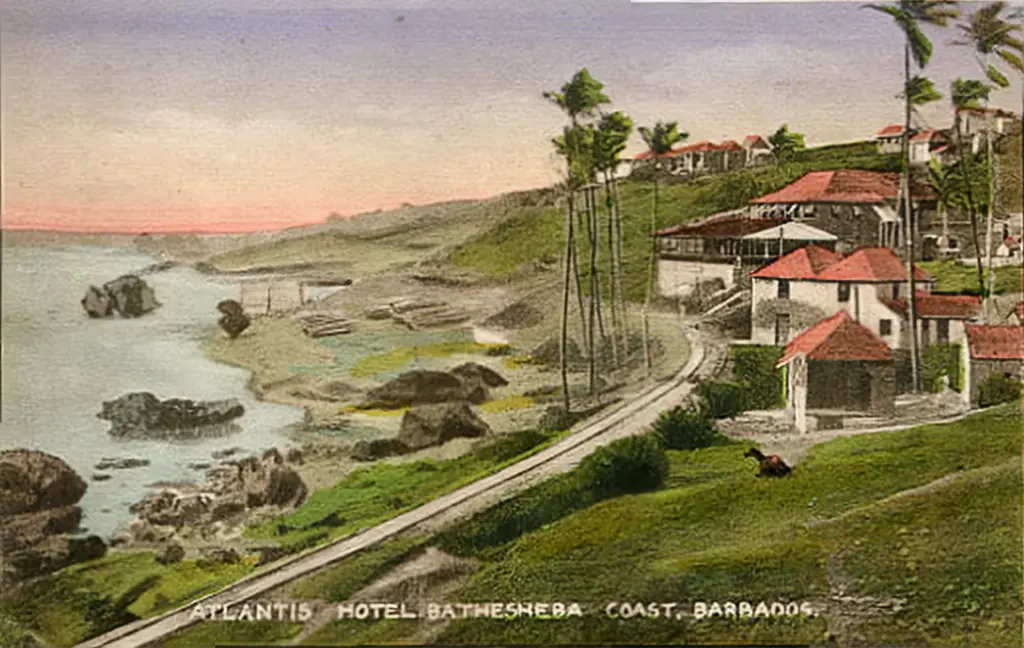

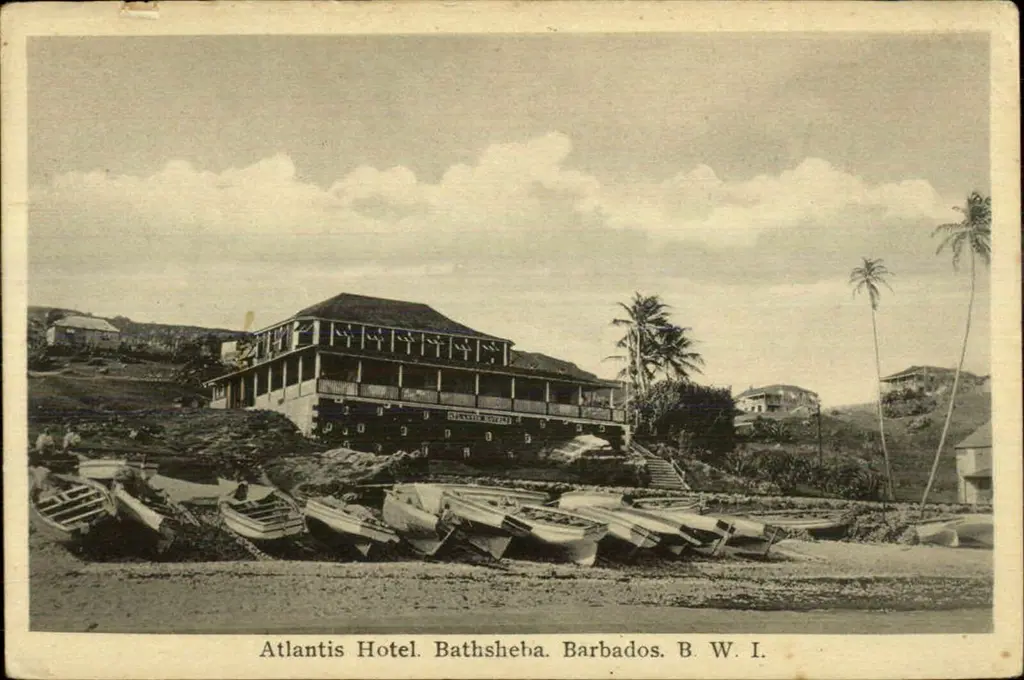

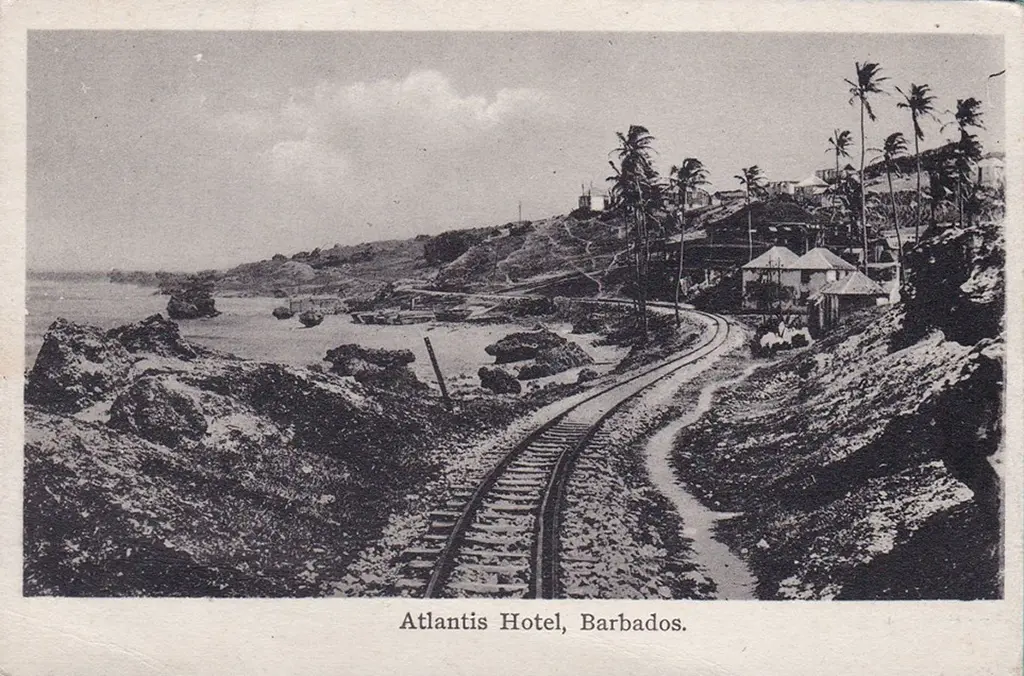

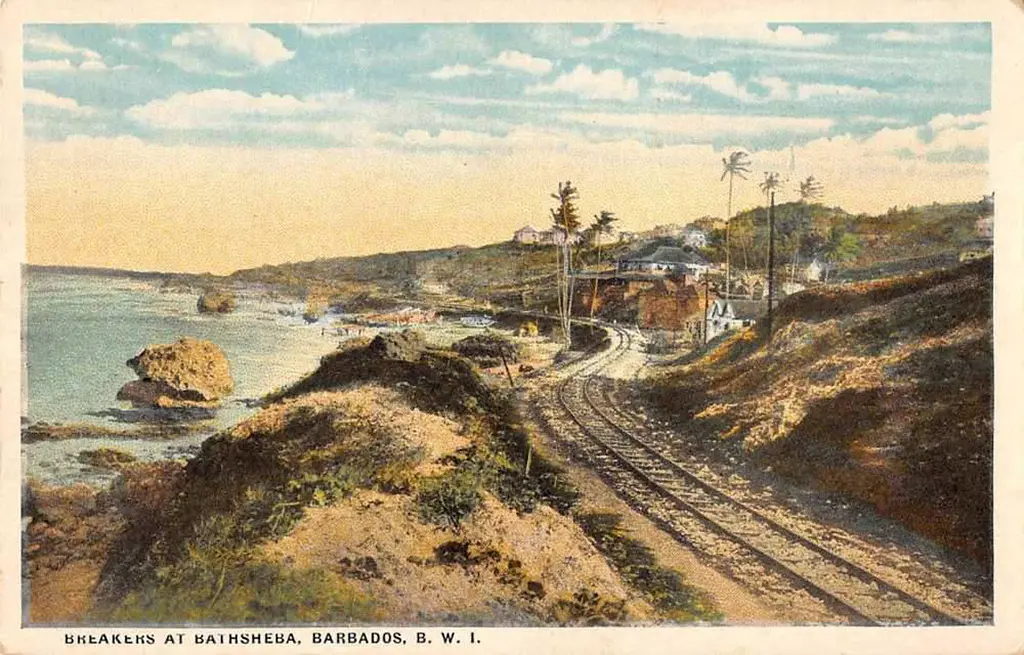

- Bathsheba – 32.2 km (20 mi)

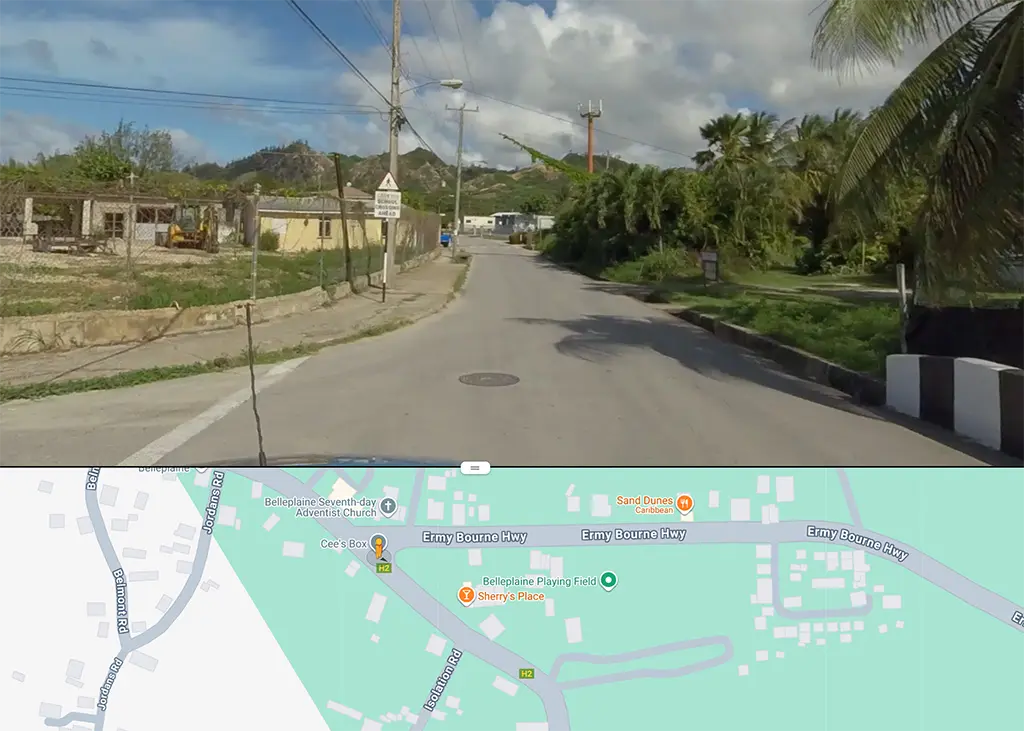

- St. Andrew’s (Belleplaine) – 38.6 km (24 mi)

Despite the turning of the first sod, legal and financial difficulties prevented the signing of the construction contract until May 1879. The contract was awarded to Leathom Earle Ross and Edward Davis Mathews Civil Engineers, London for £200,000 to “build and equip” the railway.

The specifications of the contract called for 21½ miles of main line, 3½ miles of sidings, 14 miles of fencing, 98,147 cu. yards of rock and 178,600 cu. yards of earthwork. Bridges, viaducts and culverts called for 8,283 cu. yards of masonry, 4,764 cu. feet of timber and the purchase and erection of 404 tons of girders. Rails were to be 40 lb. laid on sleepers 8 in wide, 4 in deep and 6 feet long, the gauge was 3 feet 6 inches and 2,080 sleepers were to be laid per mile. Curves were to be banked, ballasted to 1½” of top of rail.

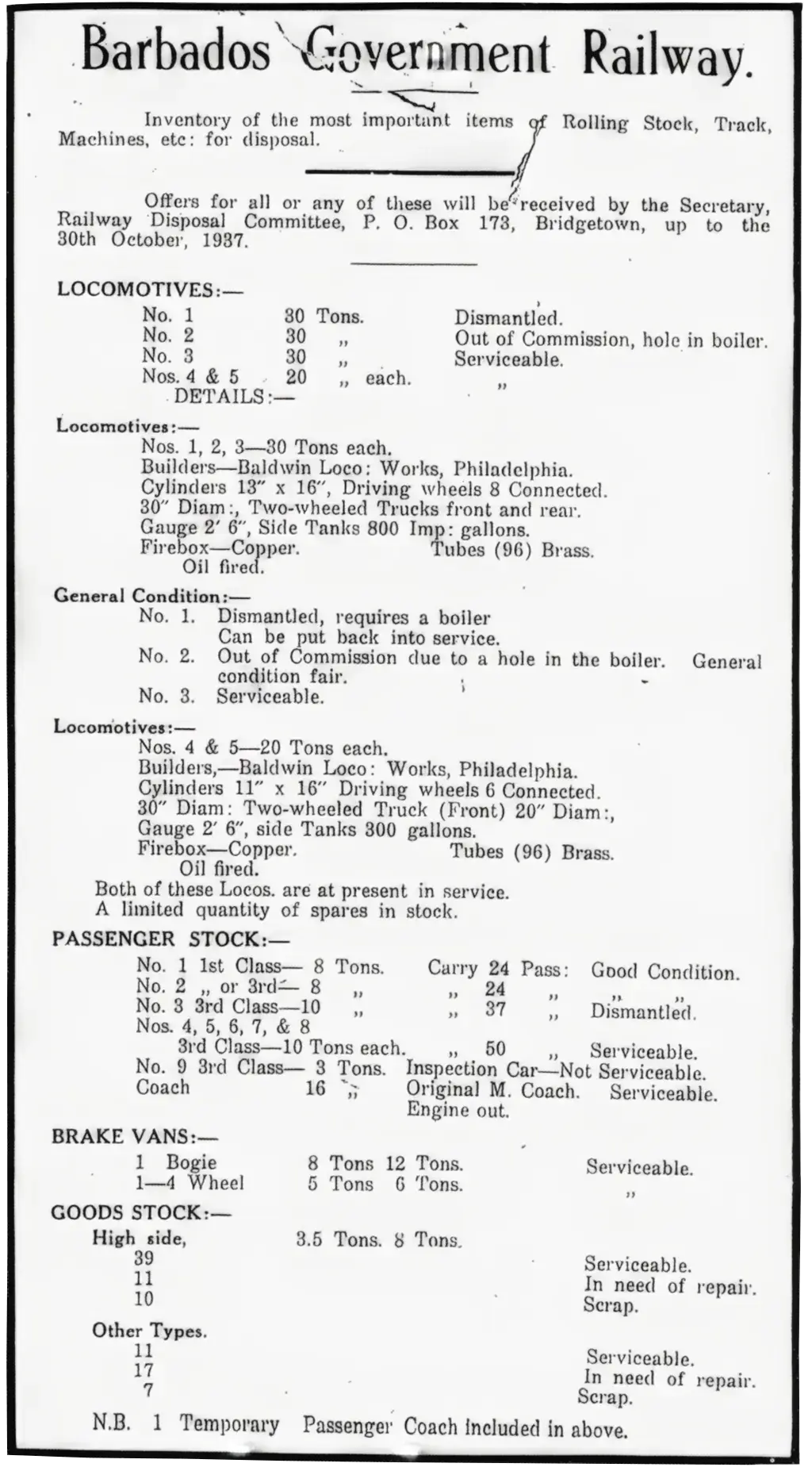

The rolling stock was specified as follows:

- 4 – locomotives

- 6 – composite 1st and 2nd class coaches

- 6 – 3rd class carriages

- 10 – open goods trucks

- 6 – covered goods trucks

- 20 – sugar wagons

All cars both passenger and goods were supplied with 4 wheels and not bogies. This was a critical mistake on the passenger cars as we will see later.

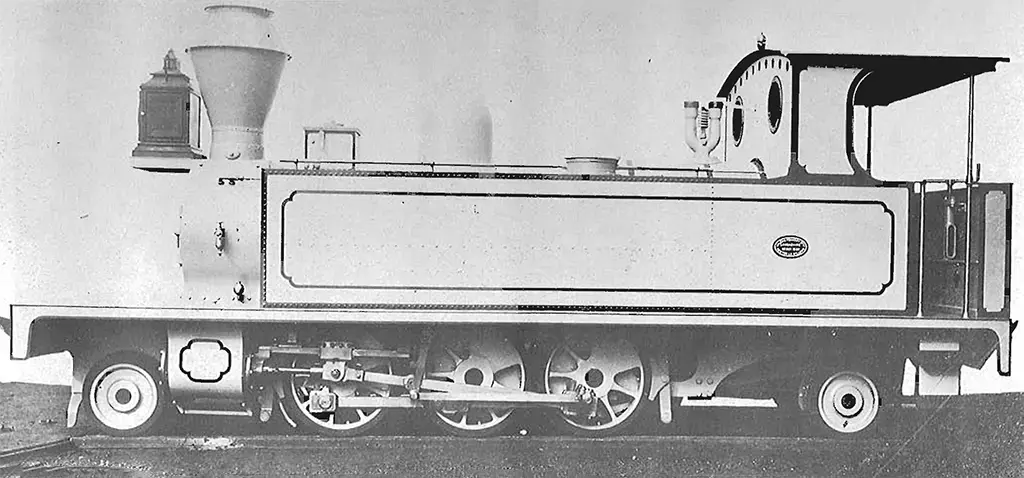

The original locomotives on the railway were the following:

- “St. Michael” Contractors engine later acquired by the railway, 0-4-0 probably Black Hawthorne No. 575, 4 ft. wheelbase with 7 inch cylinders.

- No.1 – 2-4-0 tender locomotive built by Avonside in 1880/ 1881 builders number 1286.

- No. 2 – As above, builders number 1287.

- No. 3 – 2-6-2 side tank locomotive built by Vulcan foundry in 1882, builders number 951.

- No. 4 – As above builder’s number 952.

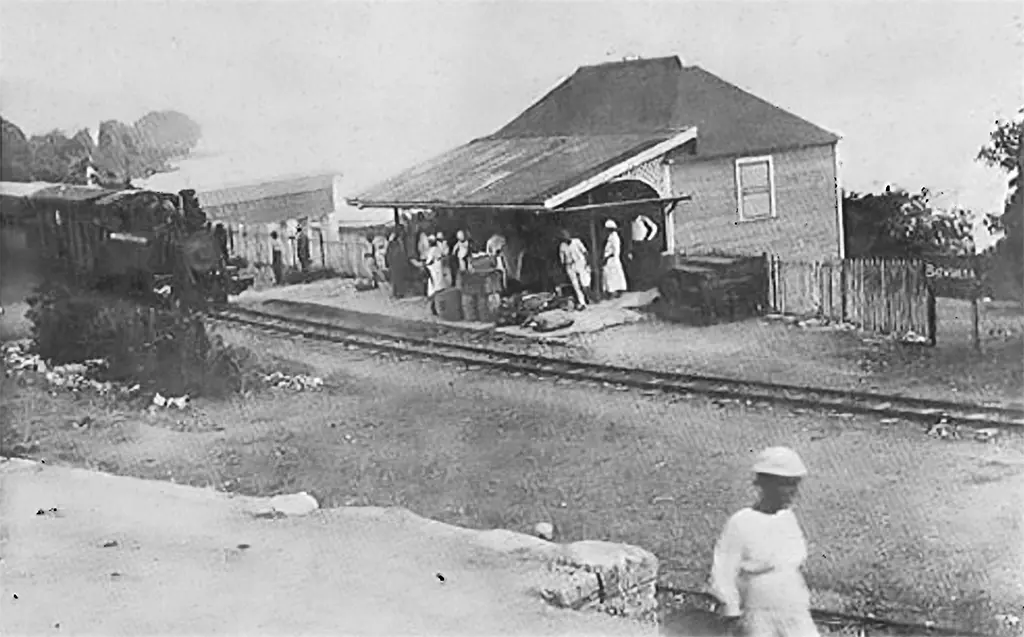

Early in 1881 the manager Mr. Grundy came to Barbados from the Great Western Railway at Paddington, a Foreman and Driver were also brought out to train local crews in the operation of steam. The railway opened from Bridgetown to Carrington on Thursday October 20, 1881 with little fanfare as Mr. Grundy had recently died of yellow fever and never lived to see the line completed. A car derailed on the first day (an omen of things to come) and service was suspended on 27th October, until 15th December, to permit the track to be “levelled”. As of 15th December, three trains in each direction operated between Bridgetown and Three Houses.

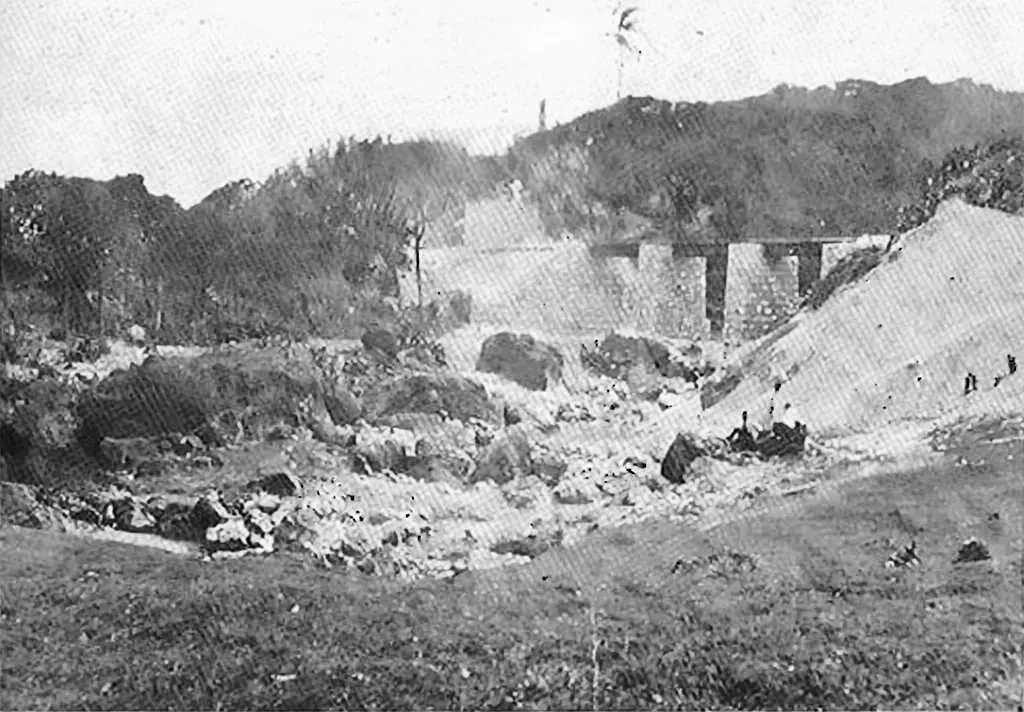

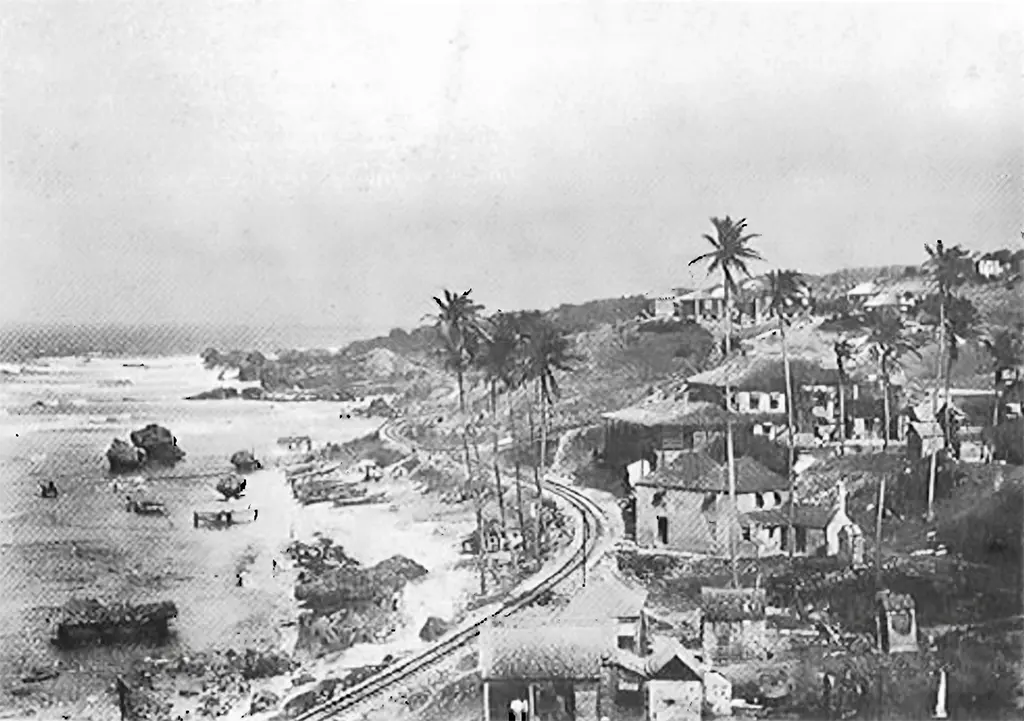

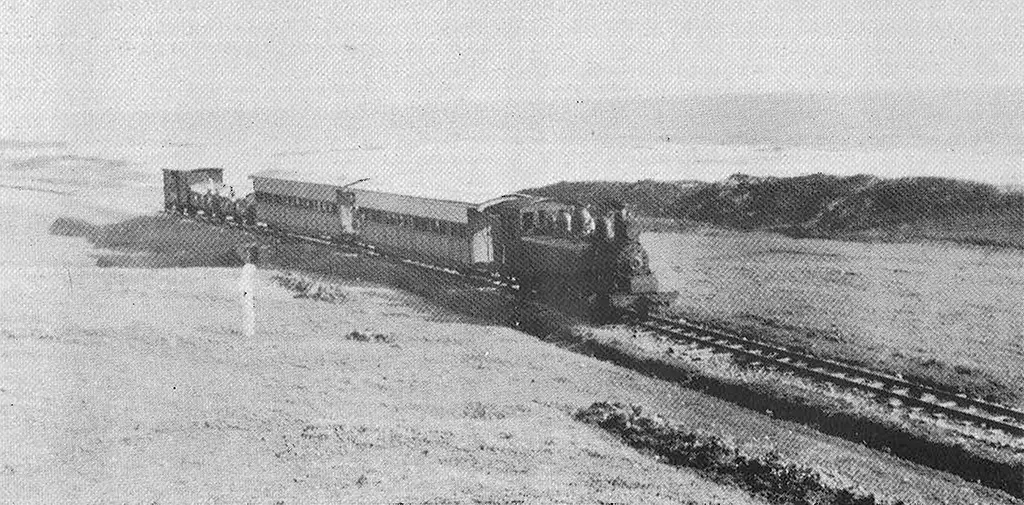

On Saturday 18th August 1883 the first train operated over the entire line . The most spectacular and indeed dangerous part of the line had finally been put into service. Just beyond Three Houses at Consetts Cutting the railway descended a 1 in 33 grade from the escarpment to sea level. This grade was to prove most challenging throughout the entire life of the railway. The grade was so steep that southbound trains had to be broken at Bath and hauled up in two sections. Passengers were often asked to alight and even push to get the train up to the crest of the incline. This embankment and grade was located on the wind swept Atlantic side (east) of the Island and was subject to vicious sea storms and erosion.

The now-completed railway line served several sugar factories along the route hauling cane wagons in and sugar and molasses out to port in Bridgetown.

Regular passenger service existed but even more important to the railway was the operation of special excursion trains and Sunday Picnic specials to the beautiful east coast of the Island. Financial records for the years 1930-1934 show that 80% of all passenger revenue was earned over this portion of the line and 50% of that was from special trains.

The company drew up its “Rules, Regulations and Bye Laws” just prior to the 1881 opening. A copy of the rules, printed in the Island by Barclay & Fraser, is still extant and may be unique as the only surviving example of a document of this kind printed in Barbados.

The Rules themselves throw some light on the original method of working which probably changed little throughout the entire history of the railway. There was a system of fixed signals operated at each station and indicating the state of the road and whether the gates had been opened; a reference to signal wires seems to indicate that signal posts were expected to be some distance from stations and indeed we know of one such signal at Halls Road which was apparently controlled from Bridgetown.

There were regulations governing the working by Train Staff and Ticket and it seems likely that this system obtained throughout the history of the line. This system is commonly applied where separate tracks are not provided for “Up” and “Down” trains and where passing can only take place at loops; specially provided. Under the system, trains can only proceed from one station to the next if drivers are in possession on the “Staff’ controlling that section. The staff was specially designed and incorporated a key which opens the box containing the tickets. A driver proceeding in possession of the staff surrendered it when he reached the station at the other end of the section; this enabled a train to proceed with the staff in the reverse direction. Where more than one train was to proceed in one direction before a train was due to arrive in the contrary direction, tickets were used to authorise drivers to proceed, the last train carrying the staff which cancelled the tickets; the tickets were kept under lock and key and could only therefore be issued by someone in possession of the staff in which the key was incorporated. There were seven sections originally and the Rule Book stipulated the colours of the staffs applicable in each case.

The rules include instructions for the ascent and descent of Consetts incline, both guards and drivers being exhorted to “have their trains well under control” and to use every “exertion to stop any runaway vehicles that may become detached from a train whilst it is ascending before the impetus has become too great” .

Guards are advised, “if the engine be defective, the sooner the train can be stopped the better” , and, “if any of the vehicles be off the rails, the breaks (sic) in the rear must be instantly applied”.

There is also a quaint injunction to guards that, “persons afflicted with insanity must not be placed with other passengers, but in a separate compartment”; it had apparently been overlooked that, as the coaching stock was to be of the American pattern, there would be no separate compartments! Guards are also to use “all gentle means to stop the nuisance” caused by drunk or disorderly passengers; if gentleness availed not, the recalcitrant passenger was to be removed at the first station, apparently by force though the rules are prudently silent on the point.

In 1891 two new 0-6-0 heavy tank engines were acquired from Bagnall’s of Stafford, they carried numbers 6 and 7. Their weight was carried over a 9 foot wheelbase and consequently severe track damage resulted. These two locomotives were disposed of in 1898 probably to the Demerara Railway in Guyana, South America who also had a 3 feet 6 inches operation and was also a British Colony at that time.

Photo collection of Mr. EA. Stoute Esq.

By 1892 the track on the East Coast was deteriorating rapidly, rains had caused landslides and bridges were suspect. Heavier rails were laid as finances permitted but the engineers were fighting a losing battle. By 1896 a petition for voluntary winding up was presented before the House, which was rejected. Track on the Windward coast had deteriorated to such an extent that “the rails have in many instances lost over one half of the thickness of their flanges, in fact some are to a knife edge.” This was, of course, due to the corrosion of materials, some of which had been in situ since the opening in 1883. At Three Houses the report states that, “rails of main line require renewing as trains have often to be backed for a good distance, and run through the Station to tackle the bank!”

The weather in November and December 1896 was notoriously bad and the railway suffered in consequence. Parts of the coastal section were almost completely destroyed and a new line had to be constructed; this so impressed the Government Inspector, Mr. Law, that he lamented that the whole line had not been built to a comparable standard.

The section between the City and Three Houses had nevertheless been improved by taking good lengths of rail out of the sidings and putting them in the main line! This was indeed a complete reversal of accepted railway practice which usually relegates worn-out rails from the main line to the sidings; such was not the state of affairs on the Barbados Railway where so many of the canons of railway engineering were, as we shall see, deliberately flouted.

Some of the difficulties were attributable to the two heavy engines bought in 1891. Engine No. 7 seems to have been the worst offender. “So long,” complains Mr. Law, “as this engine is in use, the line will never be kept in good condition and it has , in fact, actually been observed to deteriorate since the date of inspection.” Mr. Law concluded that he could not describe the line as being in proper working order though he admitted to an improvement since his last inspection; he apostrophised the rolling stock as inadequate, considered that two new engines were required for passenger traffic and thought the coaches should be of lighter construction. The whole of the permanent way needed ballasting.

Desperate remedies were called for; the petition for winding up had been rejected and additional borrowing powers were refused. The bondholders decided that a full report was necessary and they accordingly dispatched to Barbados one Mr. Everard R. Calthrop, Engineer of the Barsi Light Railway in India, to assess the position and future prospects. Mr. Calthrop’s findings were startlingly fundamental; he suggested that all basic principles of railway construction had, in the Barbados Railway, been violated” not venially only, but in the most serious degree.” The 3 feet 6 inches gauge was too wide for the inevitably sharp curves, the rolling stock was unsuitable and the axle-loads were excessive for the weight of rail.

Dealing with curves, there were three possible remedies: either the radius could be increased, or the rolling stock could be rebuilt with bogies, or the gauge could be narrowed. Mr. Calthrop unhesitatingly recommended the reduction of the gauge to 2 feet 6 inches as the best solution. Such a gauge would suit the curves and the conversion of the rolling stock could include the substitution of bogies for fixed wheelbases thus reducing the axle-loads automatically. The locomotives would have to be discarded but these were, in any case, mostly worn out.

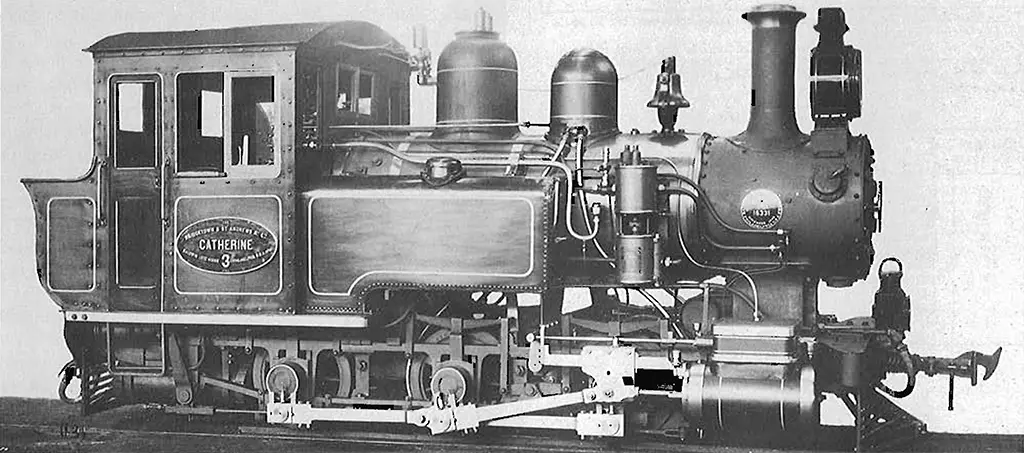

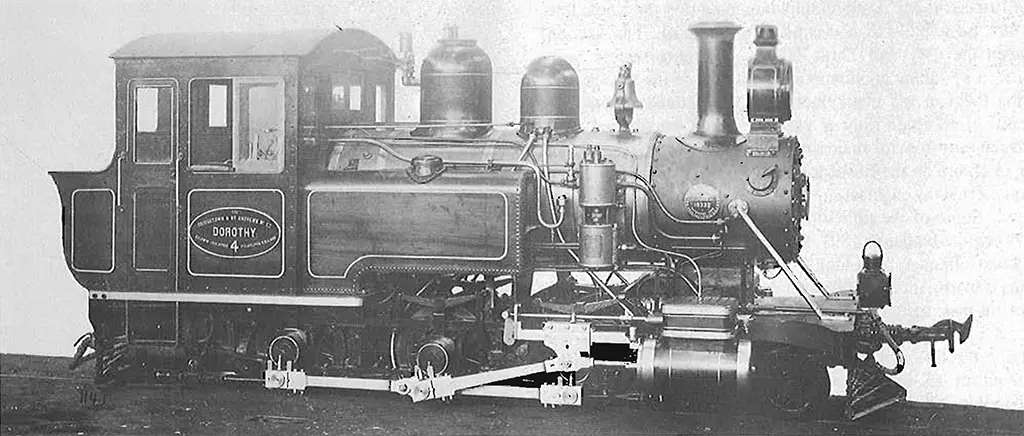

In 1898 railway service was curtailed and the company re-organised in the name of the “Bridgetown and St. Andrews Railway Limited.” The gauge was narrowed to 2′ 6″ and bogies were added to the cars locally. Four new locomotives were purchased from Baldwin in Philadelphia to serve the newly re-gauged line. A fifth Baldwin was added in 1920, all locomotives remained on the island until the end. The 2′ 6″ gauge locomotives were as follows:

- No 1 – “ALICE” 2-8-2 side tank Baldwin, 30 ton, 1898 Builders Number 16269.

- No. 2 – “BEATRICE” as above BIN 16270.

- No.3 – “CATHERINE” 0-6-0 side tank Baldwin, 20 ton. 1898 BIN 16331. Rebuilt in 1920 as a 2-6-0, converted from coal to oil and re-numbered as No.5.

- No – 3. 2-8-2 side tank Baldwin, 30 ton, 1920, oil burner BIN 52196 carried No.3 as original No.3 was re numbered to No.5 see above.

- No.4 – “DOROTHY” 2-6-0 side tank Baldwin, 20 ton, 1898, BIN 16332. All 1898 built locomotives were converted from coal to oil in 1920.

WikiMedia – Old maps of Barbados

An ambitious timetable was drawn up; there were down trains in the early morning on Sundays, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturdays and daily at 4.30 p.m. Corresponding up trains ran in the evenings of Sundays, Tuesdays, Thursday and Saturdays and there was a daily up train at 7.40 a.m.

By October, 1906, the company was complaining that many of the trains were so little patronised that they were unremunerative; in particular, all Wednesday and Thursday trains were little used. For some unknown reason, the down morning train on Saturdays had to be worked back empty and involved the company in an annual loss of £572. Total passenger receipts for that year were well below average at a mere £ 1,762 but with freight at £3,243 and the subsidy of £2,000, enough was earned to cover current outgoings.

1911 and 1912 seem to have been the peak years but, by the early war period, maintenance expenditure was inevitably mounting, and necessary repairs were being shelved with a consequent cut in subsidy in 1914. No doubt, depreciation was still being ignored, and the company was forced into liquidation, the Government finally agreeing to take over at the end of 1915.

Government’s purchase of the railway marks the opening of the final phase; £20,000 was paid for the undertaking, £15,000 being public money, the balance being raised by private subscription. After the take-over on 5th December 1916, repairs were put in hand with a consequent disruption of services. Goods traffic was resumed in February, 1917 and passenger traffic in the following August. Surpluses on revenue account were achieved in 1920, 1922, 1923 and 1927 but the intervening years were notable for large deficits so that there was a continuing drain on the Treasury.

The last of the five Baldwin locomotives was acquired at the beginning of this period and the original four, as already noted, were converted to bum oil instead of coal. All the original locomotives received their last major overhauls during the first seven years of Government ownership when they were all re boilered.

Despite Government take-over and re-gauging riding the line remained as exciting as ever, noted Barbadian Historian Edward Stoute recalls:

“I remember one Sunday when we were down at Bathsheba, we left at 4 a ‘clock by the train, and it started raining, and by the time we got to Bath it was a real tropical bucket-a-drop rain. Thunder and lightning. Going up Consett Cutting we’d get to a point where the engine would actually stop the whole train, and you could hear this rumbling, wheels spinning not holding, and the train going back down the road. She’d catch, come forward a few feet and suddenly start spinning again. Eventually, they had two boxes on the side of the engine in which they carried sand. Two of the crew got out and walked in front of the engine sprinkling sand on the railway lines for it to grip, and try to get up. That night we got back into Bridgetown about a quarter past seven.

They used to say, First Class passengers remain in your seats, Second Class passengers get out and walk, and Third Class passengers get out and push. But they only had two classes, First and Third, no Second Class. At least not in my time of travelling. The first time I ever travelled the train, I paid 2/6 to go to Bathsheba First Class.

On the next train I decided I was not going to sit down in one of those plush velvet seats; two and a half hours sitting in that and you’re soaking wet. I said “I’m not doing that, .. and went into Third Class. They had wooden seats that ran the length of the carriage, and it was very much cooler. First Class was usually empty in comparison to the crowd in Third Class”.

In a few short years the railway was again in trouble and consultants were engaged in England to access the situation.

The records of the consulting engineers, Messrs. Law & Connell, show that from about the middle of the period inadequate standards of maintenance were causing anxiety. There were complaints of the lack of brakes on the locomotives and of the system of lubricating the connecting rod bearings; these cleared the rails by only a few inches and were consequently subject to inordinate wear and tear from exposure to dust and moisture. Improper use of train brakes was a frequent cause of derailment; there was apparently a system of locomotive whistle signals to inform the member of the train crew responsible for the operation of the hand brake when it should be applied or released. There was inevitable confusion; if the brakes were not released at the rear of the train as the locomotive accelerated on coming out of a curve, the train tended to straighten itself out thus causing one or more bogies to leave the rails. There was an instance of this in 1928 at Bauva House near the 18½ mile post.

Deterioration was setting in rapidly by 1931 and a serious derailment occurred on 24th August that year when the 4:15 p.m. train from Bridgetown fouled the points at Carrington Factory siding; the consulting engineers reported that, although the switch lever was chained and locked, it could be rocked from side to side so that the tongue of the switch was clear of the rail by ⅞”, sufficient to admit the flange of any wheel.

The permanent way continued to give trouble; “I have never seen quite so much vegetation as there is at present”, bewailed Mr. Connell in 1932, though he was generous enough to admit that this might be due to two consecutive seasons of severe rain. He draws attention to the perennial lack of adequate ballasting and the chronic difficulties of cross drainage. By 1933, Mr. Connell was complaining that no notice had been taken of matters on which he had made adverse reports during the past five years and, early in 1934 he was instrumental in preventing a tourist special being run for passengers from the SS “Viceroy of India” .

On 17th January in the same year, Mr. Connell advised the suspension of passenger traffic until repairs to the Belle Gully bridge had been completed; the Iast passenger train to run was the 4:20 p.m. from St. Andrew on Saturday, 20th January 1934.

The end is quickly told; in 1934 the consultants again reported, criticising the state of the permanent way and of certain of the bridges, particularly that over the Long Pond. The carriage and locomotive sheds were described as being beyond repair whilst the locomotives needed complete stripping and overhaul. Passenger carriages were in a perilous state, many wheels having “flats” and brake systems being in “erratic” condition. All carriages required paint, “the absence of which on the entire system is most noticeable”. Stocks of spares were run down and the staff was dispirited.

Following this report, the inevitable expert was summoned from England; Mr. Gilling’s report confirms the findings of the consultants and describes the present state of the undertaking to “the failure to take reasonable precautions at the appropriate time to make good obvious damages and to provide for ordinary wear and tear” . It is the old story of the failure to provide depreciation. The track he describes as “undulating” and the rails composing it of four different sections so that the difficulties of jointing had become fantastic; this had already been noted in previous reports and it seems extraordinary that no steps had been taken to remedy the unsatisfactory state of affairs. Even the gauge needed checking since, he said, “the straight runs are full of kinks and bends and the curves made up of straight lengths having no relation to the radius”.

The Bathsheba St. Andrew section had already been closed entirely because of the failure of the Long Pond bridge. Of this bridge Mr. Gilling’s comment is, “It has either been ordered too short or there has been a bad mistake in erecting the stonework, the spans having been increasing to such an extent to make up this shortage that the bearing at the ends is inadequate for the load”.

Mr. Gilling advocated scrapping steam in favour of diesel propulsion. He regarded the coaches as unsuited to the climate and the Manager’s car was “quite unfitted for the purpose intended, it is in fact unsafe” but it could “be used as a breakdown van, it is not suitable for anything else”. Both the motor-driven inspection trollies were unsafe.

He concluded that the line was too short and covered too restricted an area; only nine of the twenty-nine factories were served. Continuing the line round the island would cost not less than £2,500 per mile. More competitive tariffs were required, and a lorry feeder service should be operated; passenger traffic might be increased by improving accommodation and by better timekeeping.

A restricted goods service was being maintained and the railway eked out a perilous existence for three more years. By 1937 conditions were such that a further report was called for and was submitted by a Mr. Bland. He confirmed the earlier findings; and he reported that one pier of the Long Pond bridge had been washed away in September 1936 with the consequence that the first span had collapsed. He did not agree that steam traction should be abandoned in favour of diesel which was, he thought, too complicated for efficient maintenance. Estimating the total cost of rehabilitation at £41,000, he concluded that, as the distances by rail compared unfavourably with those by road and as tariffs were not competitive, the railway had fulfilled its purpose and should now be abandoned.

So the death knell of the railway was sounded: but we should pause to reflect that in its earlier days the railway had performed a useful and indeed valuable function in the development of the Windward coast. Not only were the estates in that area the direct beneficiaries but the possibilities of tourism became a reality. Visitors from British Guiana and Trinidad in particular began to come to Barbados to enjoy the Atlantic breezes and one of the foremost reasons advanced for keeping the railway open in 1903 was that of tourism. The railway went into a sad decline in its later years and this was attributable to the inevitable competition from the roads; once these had been put in reasonable order, the railway was doomed as it was neither long enough nor did it cover a sufficiently wide area for it to be able to compete effectively.

The line was finally closed in 1937, the Advocate of 29th September recording that the closure meant an addition of 106 to the ranks of the unemployed. Early in the following year the scrap merchants moved in and almost all traces of the railway, other than earthworks, quickly vanished.

Today the route of the railway along the East coast can be easily traced, there remain several viaducts and cuts clearly visible. The grade at Consetts Cutting has been almost totally eroded, the cutting itself has overgrown with trees, and it is not easily located in any case.

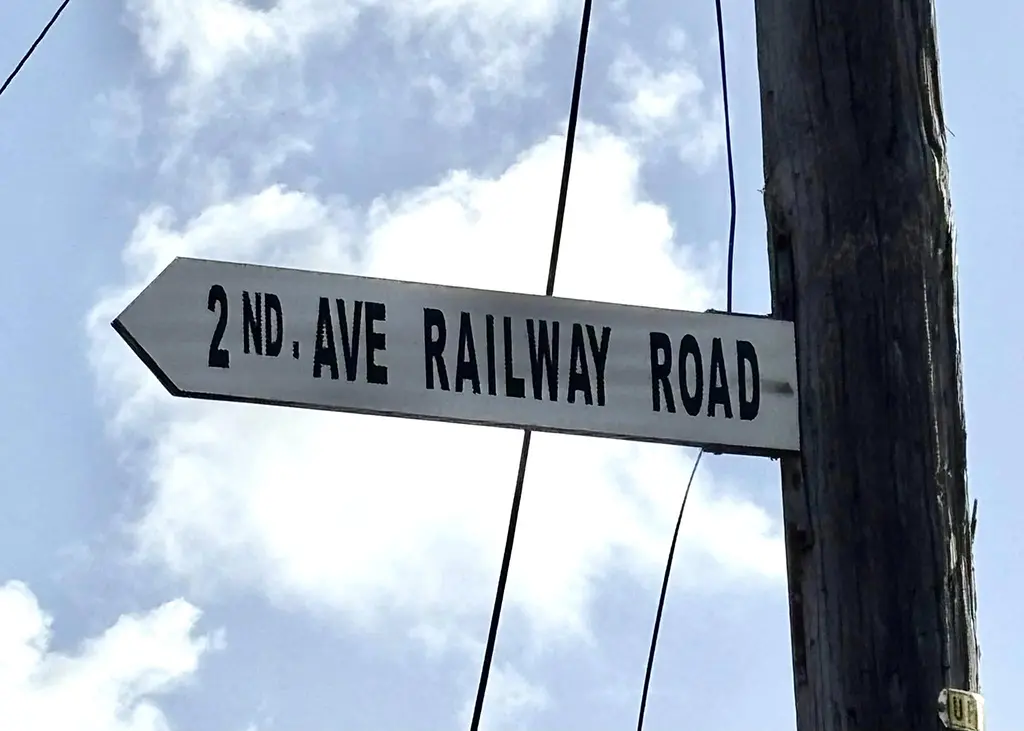

A visit to the Barbados Museum reveals the few remaining artifacts in existence: a bell from locomotive No. 1, builders plate, a mahogany and wicker chair from a first-class coach. Driving around town you might see a street called “Train Road”, which was the route of the old Barbados Railway!

Below are a series of photographs taken by the Peter Murphy in 1985 highlighting traces from the past of the Barbados Railway.

The above was taken from: “The Barbados Railway 1881-1937” by Peter Murphy, published in the Canadian Railroad Historical Association magazine; Canadian Rail in Issue 403, March-April 1988 – reproduced here with permission of the author, Peter Murray.

Below are a selection of of Barbados Railway photos used in previous BajanThings Posts.

Some tell-tale signs that can still be seen near Bellpaine of old Barbados Railway rail track used as posts:

Image taken from Google Street View with location.

A tribute to the Barbados Railway, researched and compiled by Andrew Gibbs from 2011

Most of the photographs are from book: The Barbados Railway by Jim Horsford.

This tribute to the Barbados Railway was researched and compiled by Andrew Gibbs – 2011.

The St. Nicholas Abbey Historic Railway (SNAHR)

The St. Nicholas Abbey Heritage Railway (SNAHR) is a 1.5 kilometres (0.9 mi) long heritage, 2 feet 6 inch narrow gauge railway. The railway was conceived by the owner of the St Nicholas Abbey estate, and completed in 2018. Operations officially began on 21st January 2019.

The Barbados Railway also used a narrow gauge track that was initially a 3 feet 6 inch gauge that was later changed to a 2 feet 6 inch gauge. For comparison a standard gauge railway is 4 feet 8 1⁄2 inches.

The narrow gauge 3 feet 6 inch track was developed by Norwegian Railway Engineer Carl Abraham Pihl as a way of reducing the cost of building a railway. Pihl through his international travels convinced other rural countries to build cheaper narrow-gauge systems, and the 3 feet 6 inch system soon became one of the major systems in the world; many British colonies and dominions such as South Africa, Queensland, Canada, Newfoundland and New Zealand opted for the 3 feet 6 inch gauge as did Asian countries such as Indonesia, Japan, Philippines and Taiwan.

The narrow gauge 2 feet 6 inch track was developed by British Railway Engineer Everard Calthrop for the Barsi Light Railway in India.

The Barbados General Railway opened in 1883 as a 3 feet 6 inch gauge railway from Bridgetown to St Andrew. By 1889, the railway and its rolling stock was in very poor condition. Further, much of the railway had been constructed with rail too light for the locomotives. A new company The Bridgetown & St Andrew Railway was established in 1889 to rebuild and operate the railway, and Calthrop was engaged as consulting engineer. Calthrop arranged for the railway to be rebuilt in 2 feet 6 inch gauge, and had Baldwin Locomotive Works build four new locomotives, two 2-8-2T’s, a 2-6-0T and an 0-6-0T.

In 1905 the railway again failed and was taken over by a third company The Barbados Light Railway Co. That too failed in 1915 and in 1916 the Barbados Government took over the railway which operated until it was finally closed down in 1937.

Reference Sources

- Barbados Yesterday and Today, published by The Barbados Heritage Publications Trust.

- Journal of The Barbados Museum Historical Society, February 1961 from which we have quoted liberally.

- The Bajan Magazine “Our Dear Old Train” May 1955 issue, and October 1975.

- Special thanks to Mrs. Betty Carrillo Shannon Archivist at the Barbados Museum.

- Also Mrs. Celine Barnard of the Bajan and South Caribbean Magazine, Bridgetown, Barbados.

- Special thanks to SS Worthen for his help and support in the preparation of this article. Mr. Worthen has, over the course of several visits to the island, spent numerous hours walking, driving and otherwise locating the old right-of-way.

- BajanThings would like to thank Robert Badley for sharing Peter Murphy’s article: The Barbados Railway 1881-1937 which he found in his father’s papers . Robert also made contact Peter Murphy who shared a high quality pdf which was the basis of this post.

- BajanThings would also like to thank Peter Murphy for allowing us to republish his 1988 article: The Barbados Railway 1881-1937 that appeared in Canadian Rail in Issue 403, March-April 1988.

- Barbados Railway maps.

- The Colin Hudson Great (Barbados) Train Hike

- Tent Bay, St. Joseph, Barbados

- The New Joe’s River Pedestrian Bridge.

- The Barbados Railway from BarbadosPocketGuide.com

- The History of the Barbados Railway by G. Pilkington

- The Barbados Railway by James Horsford – published in 2001. A history of the Barbados Railway, illustrated by numerous maps and black & white photographs. Includes coverage of both the 3 feet 6 inches and 2 feet 6 inches gauge eras, route description, and detailed descriptions of train services, locomotives and rolling stock.

- Barbados Railway Album on Facebook Group – The Heritage Group – Barbados, posted by Anthony Michael Hinds in 2018

BajanThings posts on the The Barbados Trailways Project, a Future Centre Trust Project who plan to convert what used to be the route of The Barbados Railway train line into a multi-use pathway for use by Bajan cyclists, walkers and runners.

Leave a Reply